Warren Buffett’s annual letter to Berkshire shareholders is always a must-read. This year’s version didn’t disappoint, with some great takeaways, as my colleague Ryan Detrick discussed the other day.

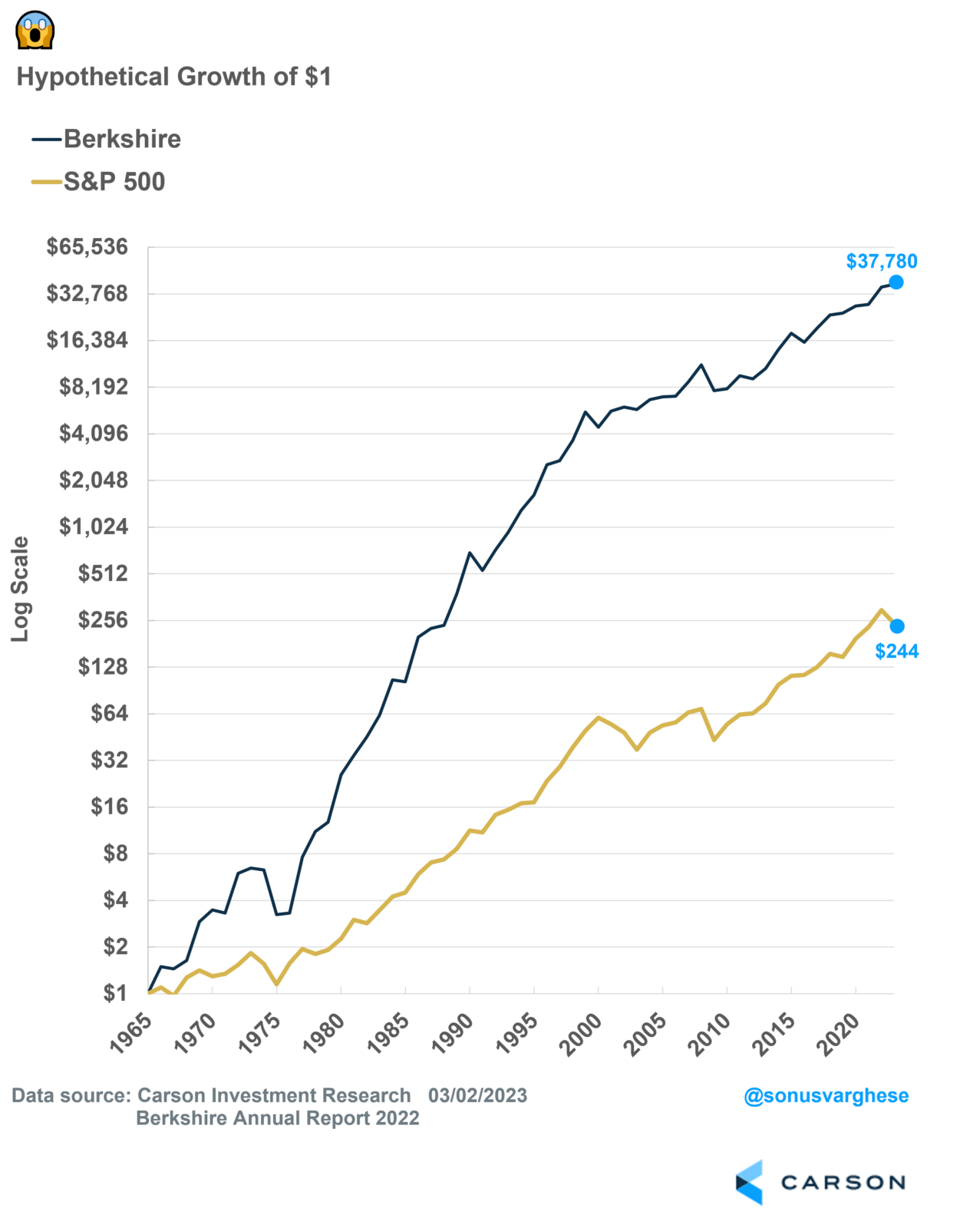

What’s particularly great is that he’s not shy to show the numbers. They’re the first thing you see, following the table of contents. From 1965 to 2022, Berkshire’s compounded annual return was 19.8%, compared to 9.9% for the S&P 500. The latter is not bad, but the former is other-worldly.

Here’s some perspective on those percentages. First, $1 invested in the S&P 500 at the beginning of 1965 would have grown to about $244 by the end of 2022, which is enormous. But the same $1 invested in Berkshire would have turned into almost $38,000 – that’s not a typo, and I double-checked my calculations to make sure.

Showing a graph with a normal scale would be meaningless since Berkshire’s performance completely overwhelms that of the S&P 500. So, here’s a log chart – which tells you how the same $1 compounded over time. Over the last 58 years, $1 in the S&P 500 doubled about eight times. The same $1 in Berkshire doubled about 15 times!

This example does not reflect sales charges or other expenses that may be required for some investments. Rates of return will vary over time, particularly for long-term investments. The hypothetical investment results are for illustrative purposes only.

But is he losing his edge?

Not really. As you can tell from the previous chart, some of the massive gains came during the first few decades. But things haven’t been too shabby since.

Over the last 30 years, i.e., 1993-2022, $1 invested in Berkshire would have grown to about $39, versus just under $15 for the S&P 500.

Over the past 20 years, i.e., 2003-2022, $1 invested in Berkshire grew to about $5.43, only slightly below the $5.49 for the S&P 500.

Keep in mind that the last decade was an especially strong one for “growth” stocks, which are not quite the type of stocks Buffett, and Munger, like to buy. Quoting Buffett from his 2008 letter,

“Whether we’re talking about socks or stocks, I like buying quality merchandise when it is marked down.”

This gels with what the researchers at AQR found when they examined his returns statistically: the general feature of his portfolio is that he likes stocks that are “safe” (low volatility), “cheap” (value), and high-quality (profitable, stable, growing companies with high payout ratios). Add about 1.6x leverage, and you get “Buffett’s Alpha.”

Sticking with it through thick and thin

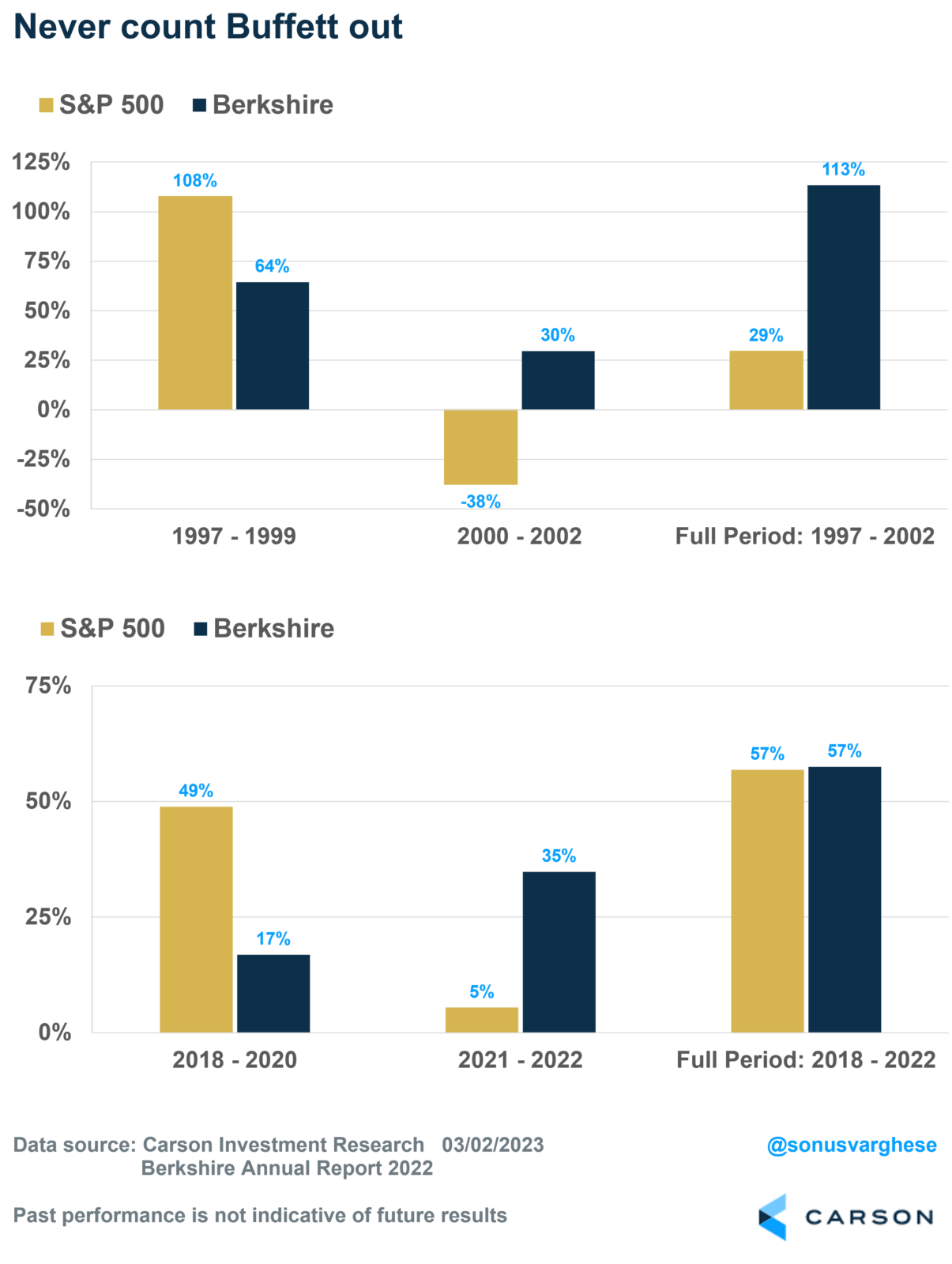

It’s one thing to know what Buffett’s done and a whole other thing to replicate it. Buffett’s been consistent with respect to picking stocks. But sticking with Buffett would’ve been quite hard, despite a solid track record of bouncing back.

Take the periods 1997 – 1999 and 2018 – 2020, for example. Both times you had Tech stocks outperforming and Berkshire underperforming the S&P 500 (by a lot, as you can see in the chart below). Most folks may have thrown in the towel at that point (as did a few magazines).

However, Buffett more than made up for lost ground post-Tech bubble and fully caught up over the last couple of years after falling behind in the 2018-2020 period.

Dividends for me, but not for thee

One thing that struck me, as it did to Ryan, was how Buffett’s investments in Coca-Cola and American Express paid him a cool $1 billion in dividends last year. And his initial investment was $2.6 billion.

Here’s what’s interesting: Buffett doesn’t pay dividends to Berkshire shareholders. And there’s a good reason why.

Dividends are a way to return money to shareholders. But so are “share buybacks” or “repurchases,” which Berkshire has done frequently (including in 2022). When a company buys back some of its shares, the total share count goes down. This means that for continuing shareholders, their interest in the business goes up. But, of course, value is added only if “repurchases are made at value-accretive prices,” quoting Buffett from his latest letter. “When a company overpays for repurchases, the continuing shareholders lose.” So, there’s nothing inherently wrong with buybacks. Again, from the letter:

“When you are told that all repurchases are harmful to shareholders or the country, or particularly beneficial to CEOs, you are listening to either an economic illiterate or a silver-tongued demagogue (characters that are not mutually exclusive).”

Here’s the other unsaid part. Unlike buybacks, returning money to shareholders via dividends involves a taxable event for the year the dividend was paid out. And the taxed amount is not available for compounding, especially when you’re compounding with Berkshire type of gains.

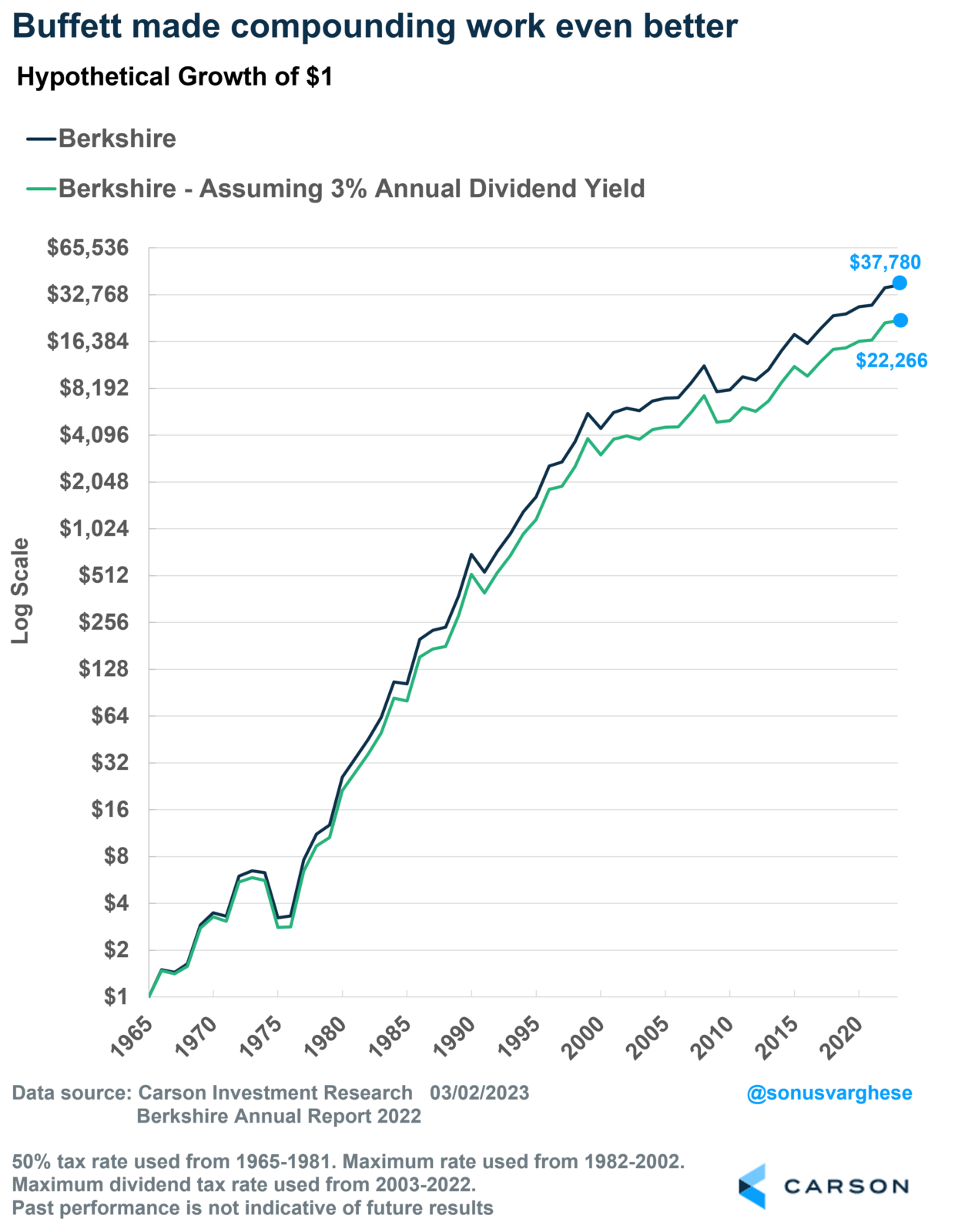

The magic of compounding, ex taxes

Amongst other things, Buffett understands the power of compounding all too well. And he understands the US tax code.

I looked at returns if Berkshire had chosen to pay out a dividend, say 3% annually from its start.

I also looked up historical dividend tax rates, which was interesting in and of itself. Up until 2003, dividends were taxed like ordinary income. And the maximum tax bracket for ordinary income between 1965-1981 was 70%. But rather than use this, I assumed that dividends were taxed at 50% during this period in our hypothetical scenario. After that, I used the maximum dividend tax rates.

Recall that the compounded annual return for Berkshire from 1965 to 2022 was 19.8%, which meant $1 invested at the beginning of 1965 grew to about $38,000 by the end of 2022.

If Berkshire paid a 3% dividend every year, the compounded annual return would have dropped by 1%-point to 18.8%, which doesn’t sound like a lot, except that the hypothetical $1 would have grown to “only” about $22,000 over the same period!

There’s certainly a lot we can learn from Warren Buffett beyond just “picking good businesses.”

Footnote: all return calculations were done using the Berkshire and S&P 500 returns data from Berkshire’s annual report for 2022.

This article should not be construed directly or indirectly as a recommendation to buy or sell any securities mentioned herein. Past performance is not an indication or guarantee of future results. Investors cannot invest directly in indices.