Another month, another strong payroll report. The economy created 236,000 jobs in March, topping expectations for a 12th straight month. A record streak that is more than double the previous longest streak (before the current expansion). That in and of itself tells you how strong and underestimated this labor market is.

Prior to the report’s release, there was cause for concern.

For one thing, job growth was hot in January and February, coming in at 470,000 and 326,000, respectively. This was well ahead of the 284,000 average monthly job creation we saw in the fourth quarter of 2022. Assuming no slowdown, March would have had to come in below 60,000 to “correct” for Jan/Feb and match the Q4 2022 pace.

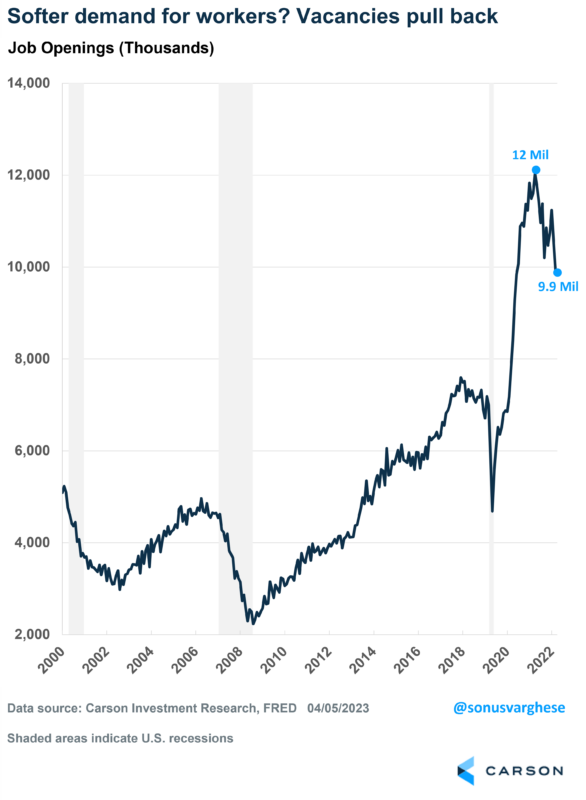

Secondly, job openings fell by 600,000 in February, to below 10 million. That is the lowest level since May 2021, and well off the peak of 12 million. While this is above the near 7 million openings we saw pre-pandemic, there was concern that labor demand was softening.

Finally, the BLS revised all their unemployment benefit claims data going back to 2018. This is typically a leading indicator for the labor market and the news wasn’t good: claims for unemployment benefits have been steadily rising since October. Again, not enough to be worried that the economy is headed for a recession but enough to be concerned.

Combine all the above with the Silicon Valley Bank crisis, and fears of a credit crunch, and you had a pessimism cocktail brewing.

Well, the March payroll report eased a lot of these concerns. Job growth in Q1 has averaged 384,000 per month, more than 20% above what we saw in the previous quarter.

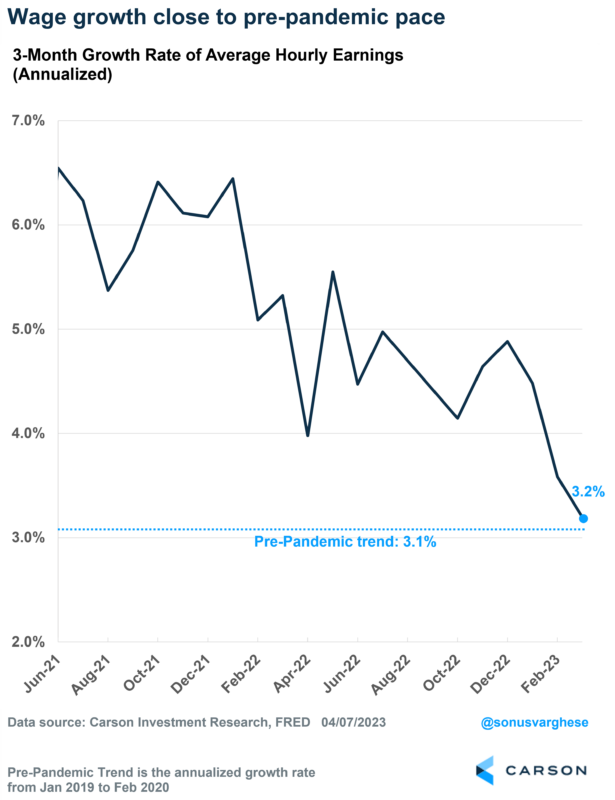

Easing wage growth should cheer the Fed

Fed officials have tied inflation, especially services excluding housing, to wage growth. And the news is good from that perspective. Over the past 3 months, average hourly earnings for private sector workers rose at an annualized rate of 3.2%, which is barely above the pace we saw pre-pandemic.

Decelerating wage growth ought to give the Fed enough reason to pause on further interest rate hikes, as inflation is likely to continue trending lower over the rest of 2023. Not to mention avoiding the risk of another banking crisis. As the Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker said:

“At this point, I don’t see why we would just continue to go up, up, up, and then go, ‘Oops.’ And then go down, down, down very quickly … Let’s just sit there for a while and see how it goes.”

What is interesting is that job growth has remained strong even as job openings, i.e. labor demand, softens and wage growth decelerates. In theory, a labor market that is less “tight” should see the unemployment rate move higher.

In fact, that’s exactly what Fed officials predict in their economic projections: inflation coming down as wage growth moves lower amid softer labor demand, while the unemployment rate moves higher to about 4.5%.

There’s theory and then there’s reality.

The unemployment rate fell to 3.5% in March. It is just a tick above the lowest rate we’ve seen in 50+ years.

So, what’s going on?

Stay on Top of Market Trends

The Carson Investment Research newsletter offers up-to-date market news, analysis and insights. Subscribe today!

"*" indicates required fields

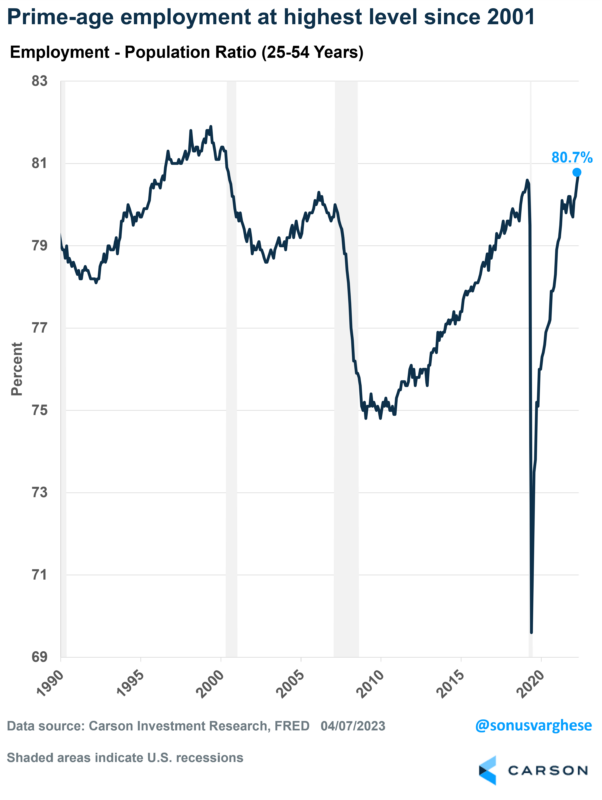

What do you know, there’s more supply

What the Fed seems to have missed is that they believed the labor supply pool is fixed. Which meant as demand for workers rose, we’d get a tighter labor market, resulting in higher wages and higher inflation.

Instead, a strong labor market is attracting more and more people to look for jobs. Just in March, almost 500,000 people came back into the labor force, and that total is 1.7 million over the first quarter!

An even better indicator than the unemployment rate is the employment-population ratio for prime age workers (25-55 years). This indicator is sort of like the opposite of unemployment. It measures employment for people in their prime-working years as a percent of the civilian working-age population. It avoids two issues:

- Lower participation due to an aging population

- Labor force classification. BLS technically classifies a lot of potential workers as “not part of the labor force”, i.e. people who aren’t actively looking for a job (irrespective of the reason).

The measure rose to 80.7%, which is the highest level since 2001.

Here’s a statistic to underline all of this: the employment-population ratio for prime-age women just hit 74.9%, which is the highest level in U.S. history!

Could things change? Sure.

But for now, the labor market is the strongest we’ve seen in a couple of decades. That’s your takeaway.