Last week Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said that the Fed is focused on its job of getting inflation down to their 2 percent target. As I wrote at the time, he also noted that there would be an unfortunate cost, as getting inflation back to target will bring pain to households and businesses. Put simply, the Fed achieving “price stability” would be accompanied by rising unemployment.

Well, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported this morning that the unemployment rate rose from 3.5% to 3.7% in August. So, are we starting to see signs of the pain Powell mentioned?

Not really. The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed persons (those who are looking for a job) by the size of the labor force (employed + unemployed). In August, the ranks of unemployed increased, but not because more people were laid off. It was because more people came back into the labor force and started looking for jobs. This is actually a good sign; in that it points to a more attractive labor market. Certainly not something you see in a recession.

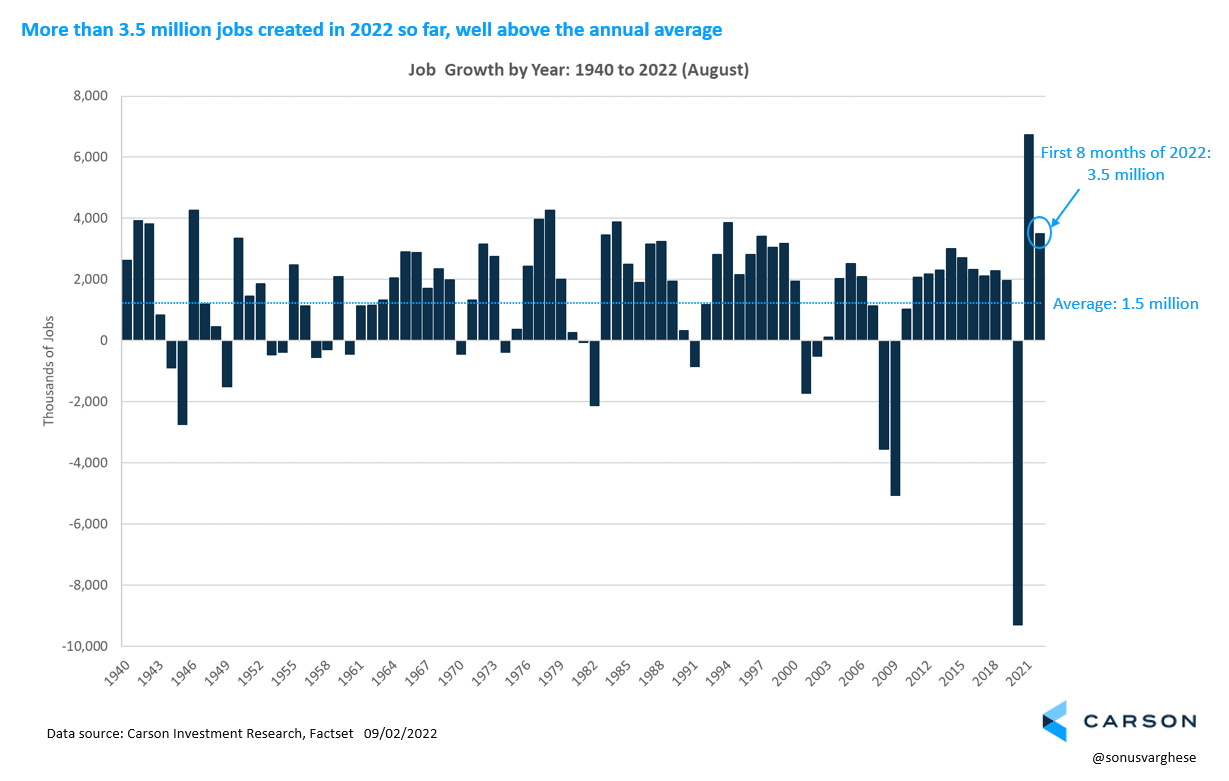

The economy created 315,000 jobs in August. These numbers can get revised and so its useful to look at the average over the last 3 months – job growth averaged 378,000 each month between June and August. Outside of immediate post-recession recoveries, when we would expect job creation to be high (like in 2021), you have to go all the way back to 1994 to find a number this high.

The economy has created 3.5 million jobs this year, and we have 4 months left to go. Average annual job growth since 1940 is about 1.5 million, and 2.3 million if you exclude recessions. Folks, this is a very strong labor market.

But why is Powell talking about pain anyway?

It helps to back up bit. The Fed has a “dual” mandate imposed by Congress: price stability and maximum sustainable employment. The word sustainable is key here, because there is a potential tradeoff; as employment rises, and in an unsustainable way, prices go up at a faster rate.

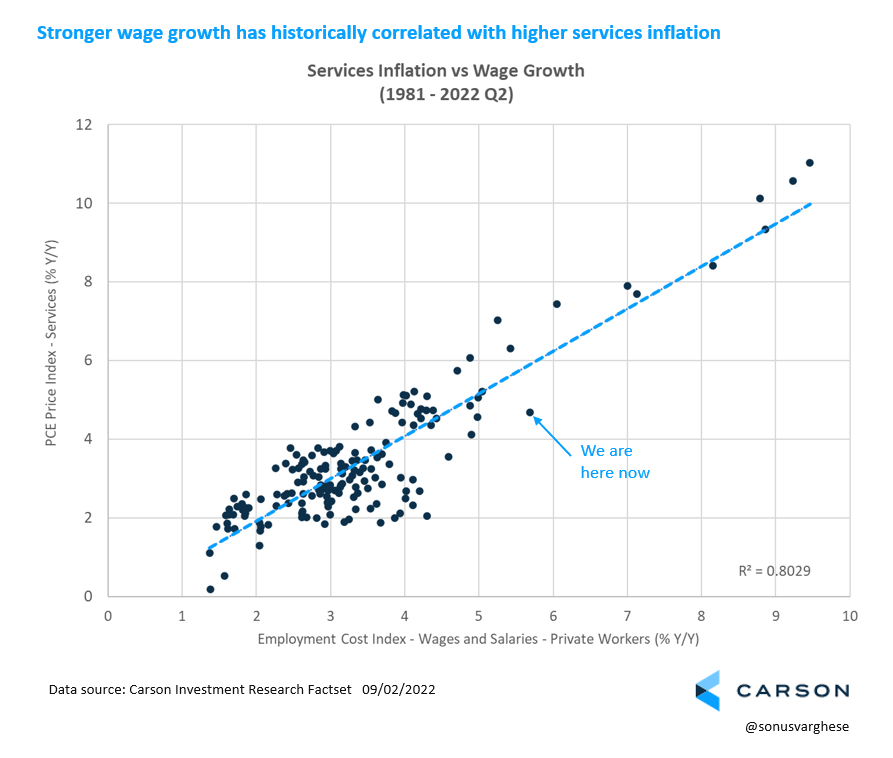

Now the connection between employment and prices is through wage growth, at least as the Fed sees it. And there is good reason for this. Inflation can be impacted by several factors, including global oil and food prices, and supply-chain disruptions – as all of us are probably quite familiar with at this point. If you strip out goods that are impacted by these sorts of factors, we’re mostly left with services inflation. This is what the Fed is really concerned about. And as you can see in the chart below, strong wage growth has historically led to higher services inflation.

To help with some intuition here, a big part of services inflation is rents. If workers are seeing large wage increases, landlords may be more likely to raise rents. Which could lead workers to ask for even higher salaries. There’s bit of a chicken and egg situation here, but you can see how this could spiral out of control with the Fed losing ground on “price stability”.

To avoid the potential out-of-control spiral, the Fed sees its job as to keep a lid on wage growth. And the best (and to be honest, blunt) way to do that is to weaken the labor market, as Powell openly admitted. If the labor market is weakening and unemployment is rising, employees may be reluctant to ask for raises.

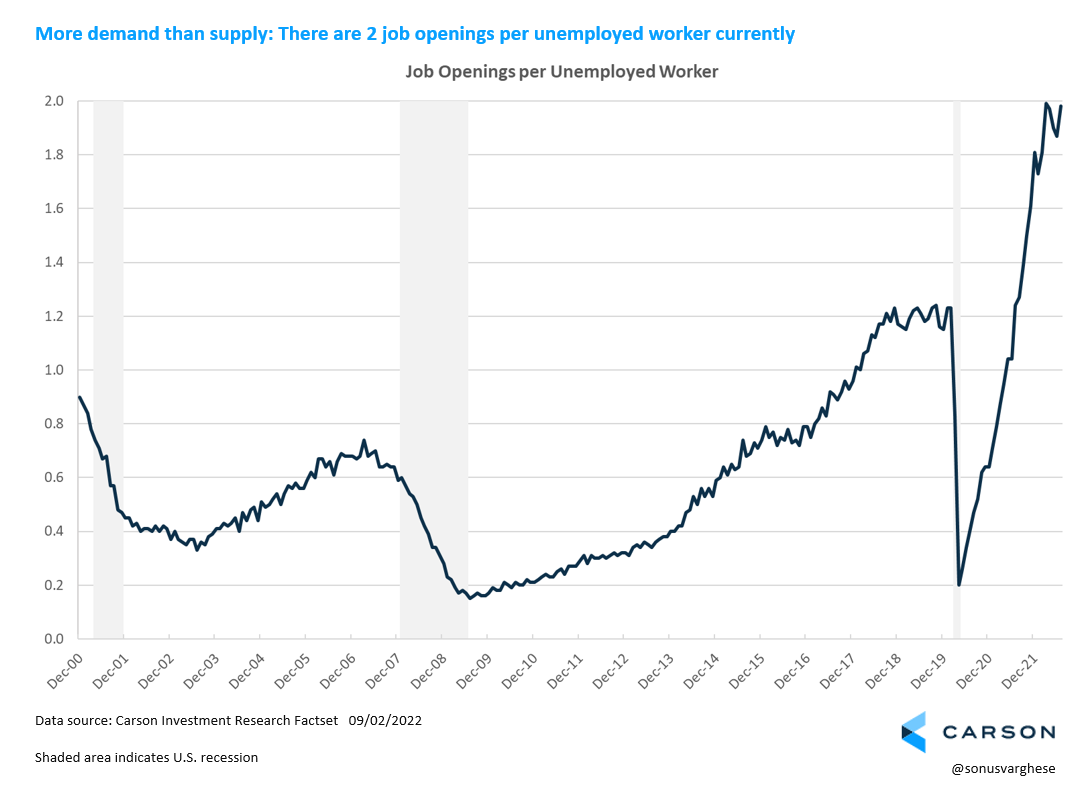

But right now, the labor market is anything but weak, and there is a big supply-demand imbalance. Job openings listed by employers are running twice as high as the number of unemployed workers. Before the pandemic the ratio was about 1.2, i.e. 12 jobs listed for every 10 unemployed workers, versus 20-to-10 right now. So, employers must pay a lot more to find workers. Powell and company would like to see the line in the chart below fall and fall by a lot – bringing the supply of potential workers back into balance with demand.

Wage growth is slowing anyway

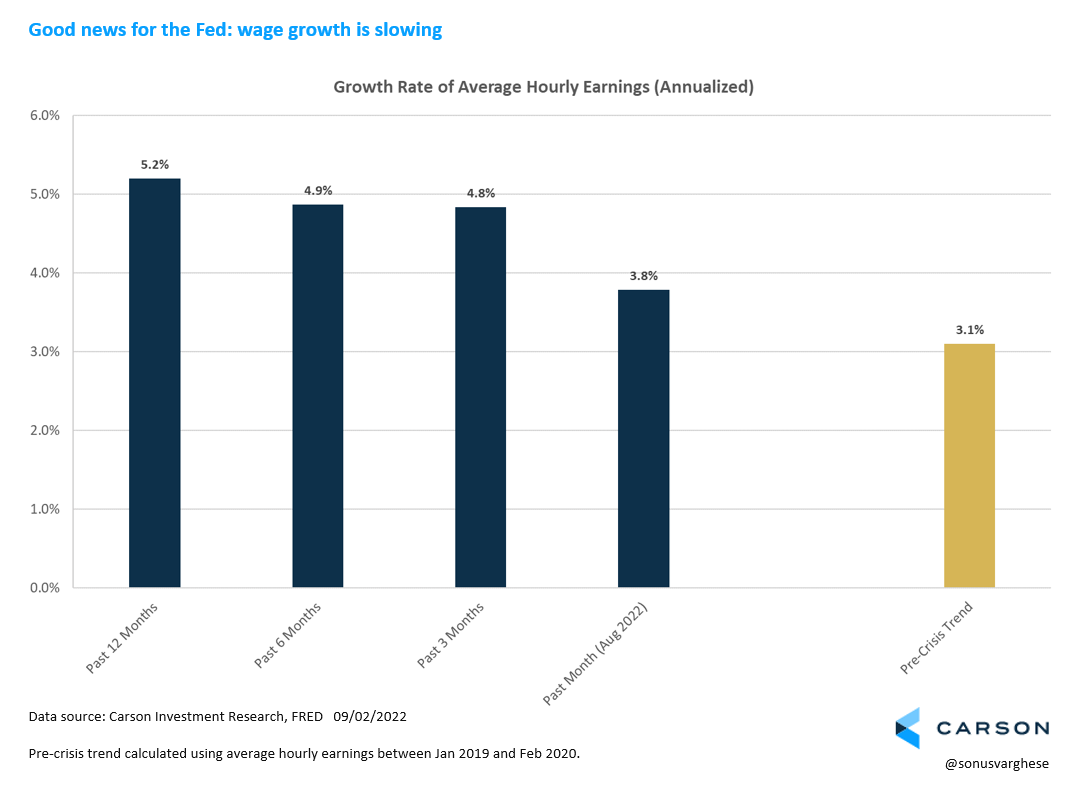

Average hourly earnings for private sector workers rose about 4% (at an annualized rate) in August, which is slower than the 5% rate we’ve seen over the past year. It appears to be moving closer to the pre-crisis wage growth rate of about 3%.

Obviously, slower wage growth is not great news if you are employed, given how high inflation is. Though we seem to be getting some relief on that side too, especially with gas prices falling. But from the Fed’s perspective, the best news in the August payroll report was that wage growth slowed.

Wait, how is this happening?

The typical belief amongst a lot of economists (and prominent ones) is that for wage growth to slow, job openings would have to fall – leading to slower employment gains, and ultimately, higher unemployment.

So far, we’re not seeing it.

Wage growth slowed even as job openings remain very high. Employment gains did slow in August, but it was always unlikely that job growth would continue running at half a million a month. Moreover, layoffs remain at record lows. All this is exactly the opposite of what would be expected.

While its hard to pinpoint an exact reason, one big factor may be that the economy is continuing to normalize after two years of massive pandemic-related shifts.

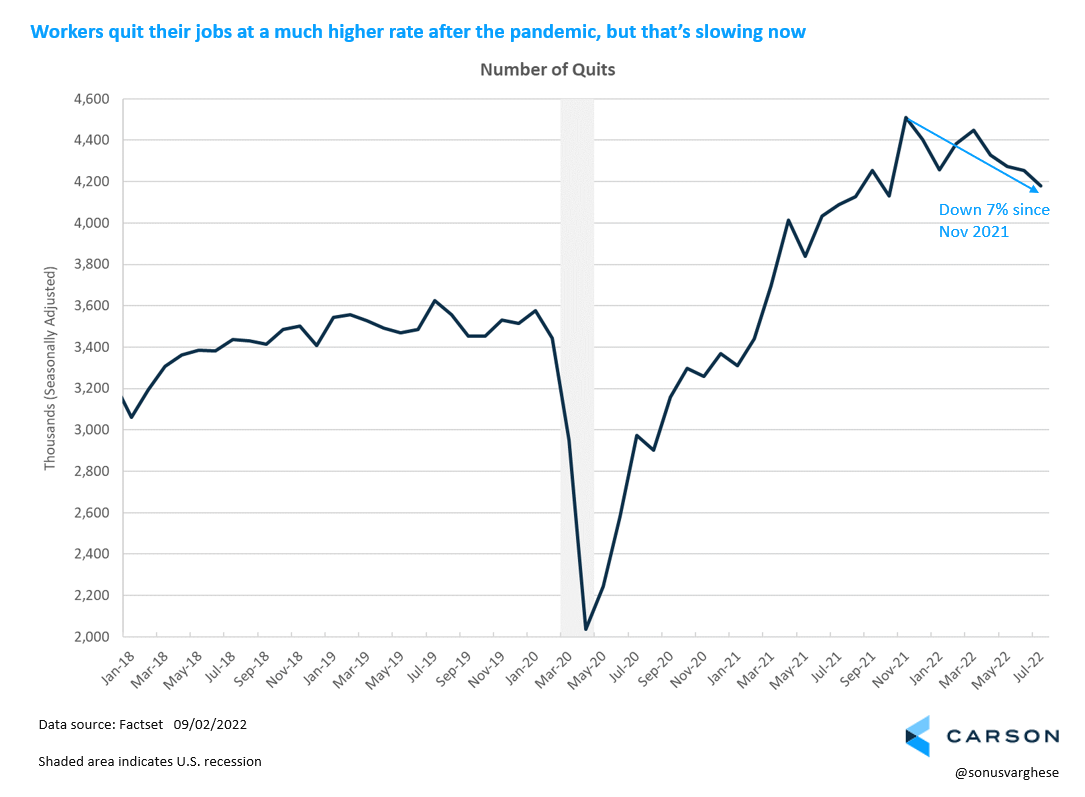

Soon after the pandemic, we saw workers voluntarily quitting their jobs at a much higher rate than pre-pandemic. Some people termed this as the “Great Resignation”. But it was really the “Great Job Switch”. Workers did not quit their job to stop work. Instead, they quit to take another job – and importantly, one with higher pay. Over the 12 months through July, “job switchers” saw wage gains of 6.7% on average, compared to 4.9% for “Job Stayers”. This is the largest difference since 1998, when the government started keeping track of the data.

We’re going the other way now in terms of quits, perhaps as the economy normalizes. Quits are down 7% since last November, with most of that occurring over the past 4 months. Which may be why wage growth is declining without unemployment rising in a significant way.

There is no way to tell whether this will continue. If you look at the chart again, you can see that quits are still well above what they were pre-crisis – pointing to a strong labor market. Workers are unlikely to quit their jobs at these rates if they thought they couldn’t find another job quickly. But it also means there could be more room to fall, and for this “painless rebalancing” to continue.

It would be the ideal case for the Fed, and really for the economy. If wage growth continues to fall, that is a good sign for the services part of inflation. It also means the Fed would not have to increase rates too much further from here. And if all that happens on the back of fewer quits, as opposed to rising unemployment, that would indeed be the best case.