First, the good news –

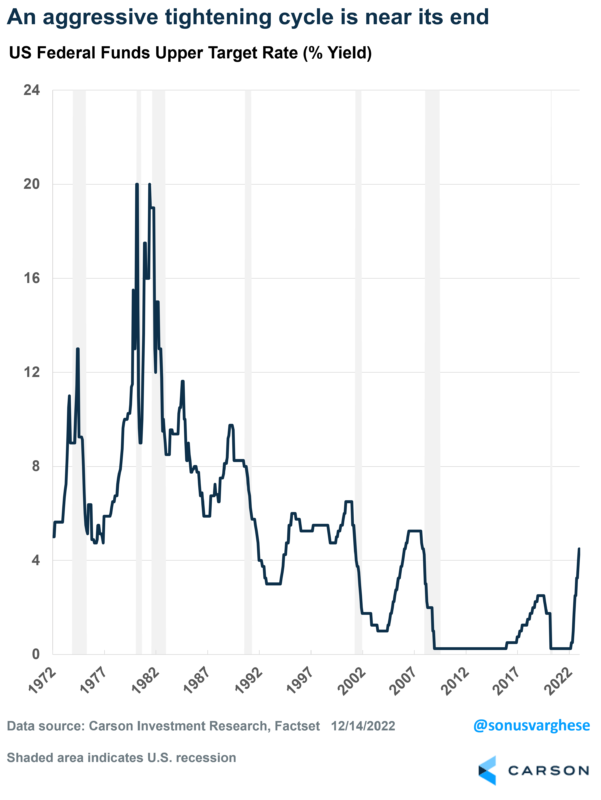

- The Federal Reserve raised the Federal Funds rate by 50 basis points (bps) to the 4.25-4.50% range – a step down from the 75 bps rate hike pace they went with at the last four meetings. This was expected, but it’s always good to see confirmation.

- They also said that “ongoing rate increases will be necessary” and raised their estimate of the peak rate from 4.6% to 5.1% in 2023, which was not a big surprise. What’s important is that the end of the rate hike cycle is near. The estimate revisions are nowhere as large as what we had seen earlier this year. At the end of 2021, they estimated rates to peak at 2.1% and then continuously shifted those up by 0.6% – 1% increments every three months.

The not-so-good news: They also provided revised estimates for the economy, which wasn’t great.

- They revised economic growth lower, from 1.2% to 0.5% (2023)

- They revised the unemployment rate higher, from 4.4% to 4.6% (about 1% point higher than where it is now)

- They revised core inflation higher, from 3.1% to 3.5% (2023)

While Fed Chair Powell was careful to say that they don’t believe these forecasts qualify as a recession, keep in mind that the U.S. has never experienced a 1% rise in the unemployment rate outside of a recession.

But if you notice, I said “not so good news” instead of “bad news.” Powell pointed out that these are members’ best estimates “as of today,” but that could change as new data comes in. And we have plenty of data coming in. Before their March meeting (when they update the projections again), we have three more inflation reports, three employment reports, and an employment cost index report (which is a preferred gauge of wage growth).

If you look back at the previous chart, we’ve seen significant shifts in rate expectations just over the course of this year. There’s no reason to think we won’t see more revisions if the data cooperates.

The shift: From how fast and how high to how long

The conversation in 2022 revolved around inflation, which surged to the highest level since 1981. As a result, we saw the most aggressive monetary policy tightening cycle in four decades as the Federal Reserve (Fed) looked to get on top of inflation. The Fed’s singular focus was to ensure they did more than “enough” to lower inflation. Consequently, the over-arching question on investors’ minds across the year was how quickly the Fed would raise rates, and how high they would go.

I believe that’s going to shift in 2023. Fed officials will likely start thinking about balance again: the risk of tightening too much vs. the risk of not doing enough. Powell mentioned this in comments he made a couple of weeks ago but didn’t mention it again in his post-FOMC meeting press conference. The omission was curious, more so because we just got a second consecutive inflation report that surprised us to the downside. All he said was that, while the report was encouraging, they need substantially more evidence to believe that inflation has turned a corner. And so, they’ll keep rates “sufficiently restrictive.”

I think it was probably more a matter of Fed officials not having enough time to digest the report and not revising estimates accordingly. But as I wrote, the prospects of softer inflation in 2023 look good. There is enough reason to believe that disinflation will kick in as we get into the backend of 2023, especially if energy prices don’t spike again and core goods prices continue to ease. Official rental inflation starts to reflect market rents (which are falling rapidly). All of which makes it likely that estimate revisions will happen.

So, the question for investors will also shift—from how fast and how high to how long and how long they will keep interest rates at an overly restrictive level. The conversation will revolve around how many months of soft inflation data they need to see and how soft it must be. This could obviously take some time since inflation is not going to go down in a straight line – there may be fits and starts and false alarms, but the trend is clear.

The risk of “transitory” deflation

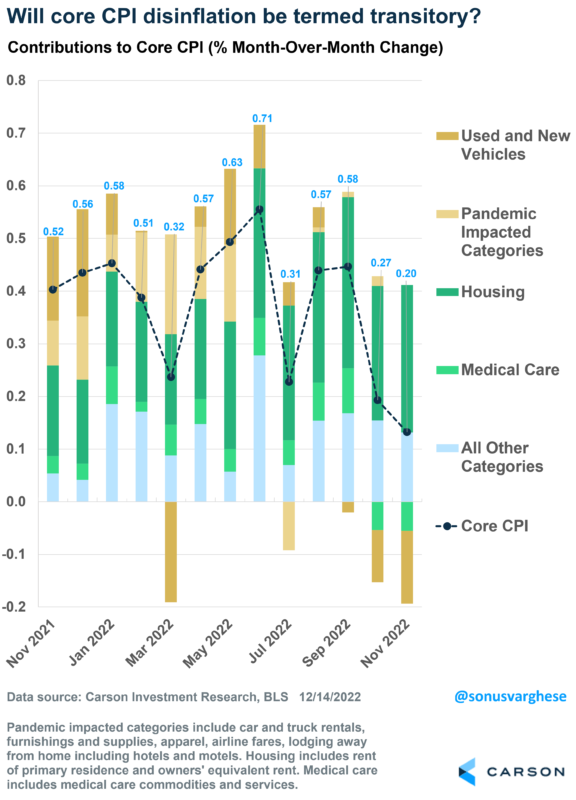

What will upset the apple cart is that the disinflation we see in goods prices and housing is deemed transitory by the Fed, and they maintain rates at an overly tight level. This is not an insignificant risk. Powell again mentioned core services inflation, excluding housing in his press conference. He tied it to wage growth and a tight labor market. This group includes personal care services, education, childcare costs, wireless services, insurance fees, etc. – all captured in the light blue bar in the chart below.

As you can see, the good news is that the light blue bar just made its lowest contribution to core inflation in four months. The risk is that the Fed looks past all of this. Instead, they use wage growth and other labor market metrics as their guiding light as they think about “how long to stay restrictive.”

I think the odds are weighted in favor of them moving lower once inflation starts to fall rapidly, though only by the end of 2023 at the earliest. Which is not as early and not as big cuts as the market currently expects.

Be sure to listen to our latest episode of the Facts vs. Feelings podcast. This week we chatted all-things commodities with Kathy Kriskey of Invesco. So much great information packed into that 30 minutes.