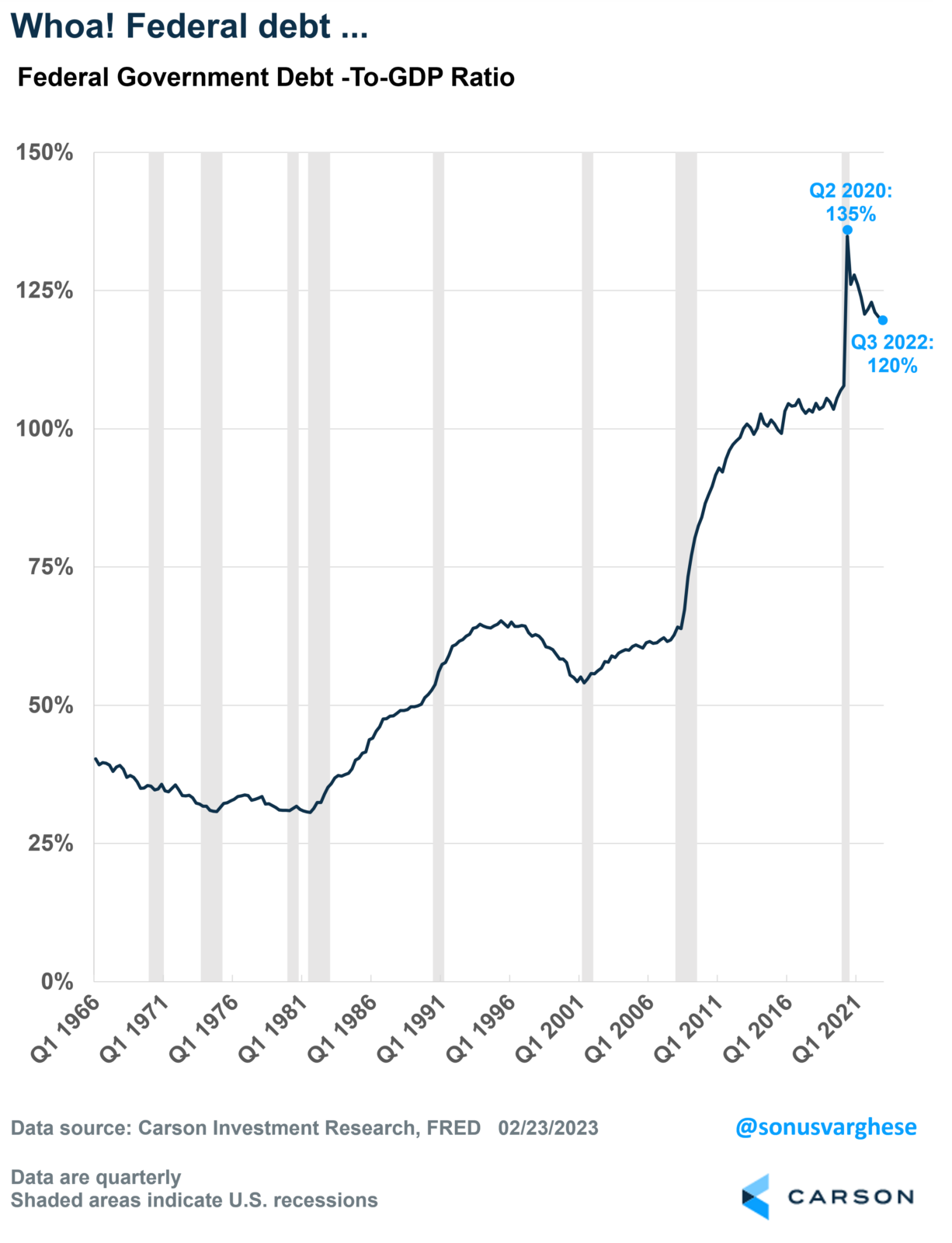

The US national debt is about $31 trillion right now, which is equivalent to about 120% of GDP (as of the third quarter of 2022). Massive, but also note that this is down from a peak of 135% in the second quarter of 2020.

Here’s the thing though: looking at debt-to-GDP is sort of like calculating your mortgage balance-to-income ratio. Using the average mortgage debt of $346,000 as of September 2022 and median household income of $71,00, the “debt-to-income” ratio is just under 500%! There’s a reason nobody quotes this number. Of course, GDP is not technically the government’s “income” – only a portion of it is (via taxes).

Anyway, what really matters is the government’s (or households’) ability to service their debt. And interest rates are a key variable there.

With rising interest rates, how can the US manage its debt service?

This is a frequent question that we get.

The short, perhaps glib, answer is Yes. The US can always “manage” debt service because it prints its own currency. And that’s a crucial difference to understand between the US government and you and me – we can’t “print money” to pay off our debt. Or rather, we can print IOUs, but nobody will accept them.

In all seriousness, US treasuries are considered the safest asset in the world, which includes the belief that the US government will not simply “print money” to service and pay back its debt. So, let’s consider the question of whether the US can manage its debt.

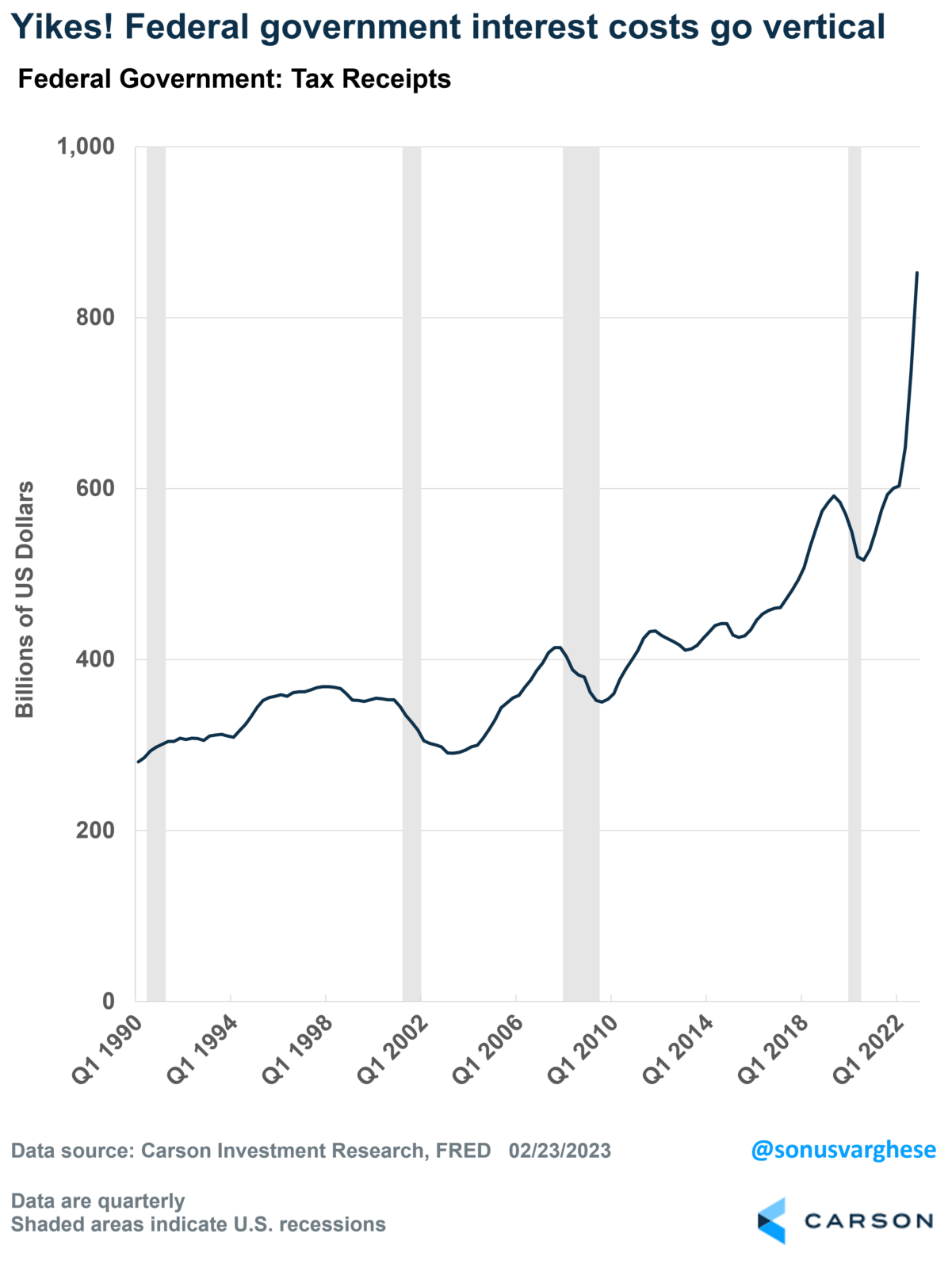

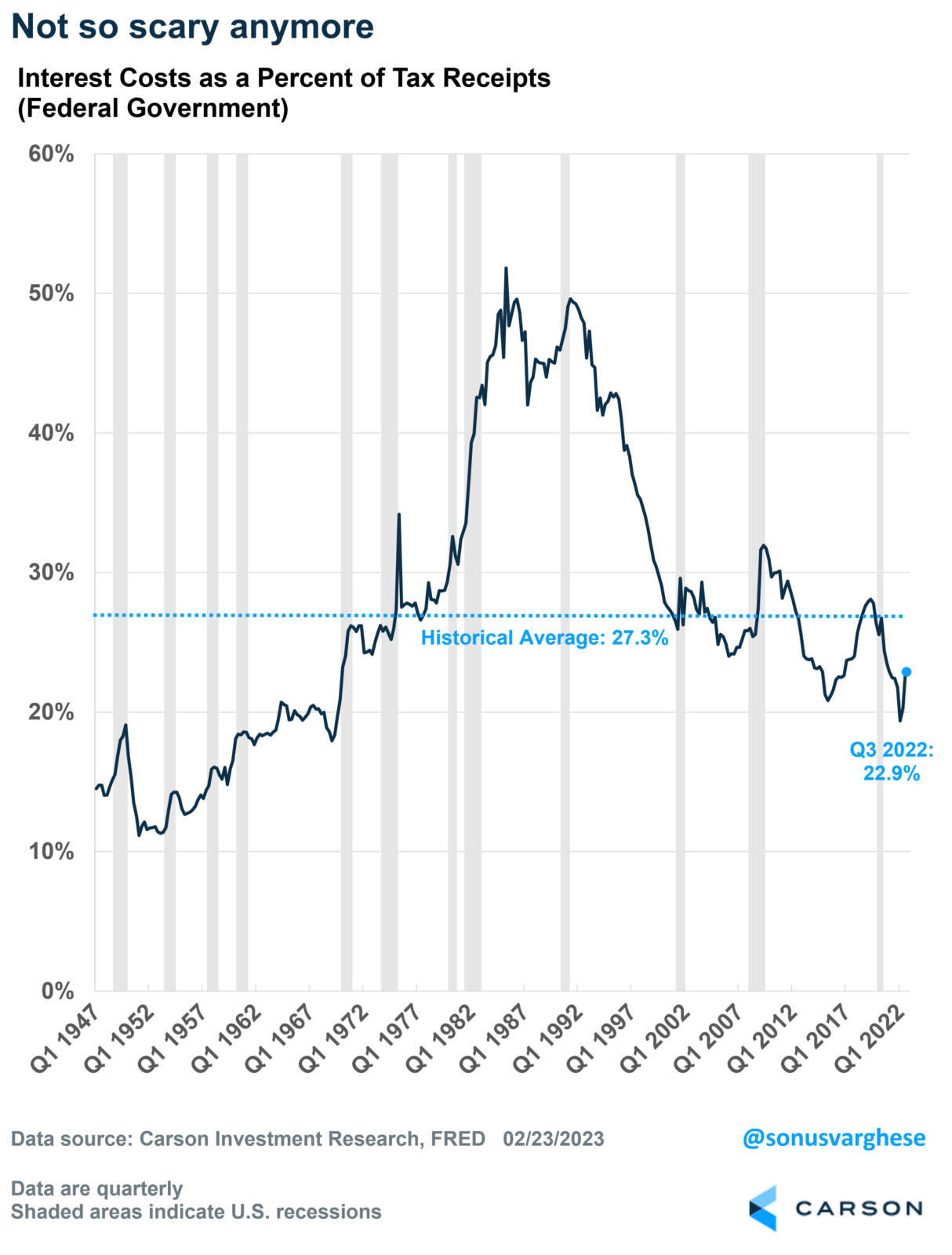

As you can see from the chart below, interest costs for the Federal Government have exploded higher. This is due to rising interest rates as well as the massive increase in debt over 2020-2021.

The other side of the story

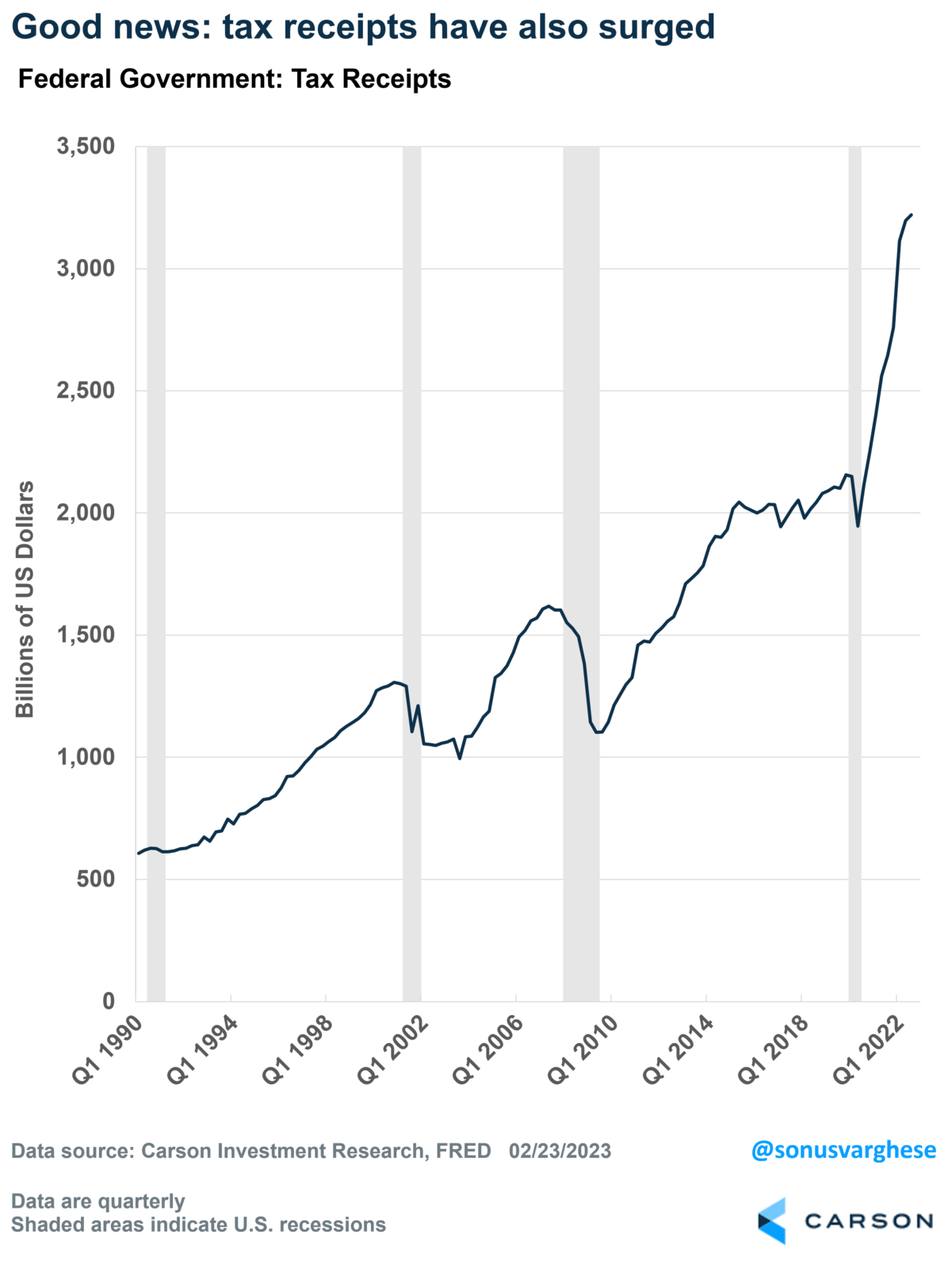

The good news is that tax receipts have also exploded higher recently. Of course, rising employment helps a lot – there’s a bit of a round-trip here, with fiscal stimulus helping maintain spending and employment, which in turn is holding up tax revenue. Plus, the stock market has moved up a lot in 2020 and 2021, which means capital gains taxes have also increased.

If you look at interest costs as a percent of tax receipts, things don’t look as scary. The ratio has risen recently to about 23%, but that’s well below the historical average of 27% (from 1947 onwards).

What’s interesting about the chart is that you can see that the ratio surged in the early 1980s. That’s because the Volcker interest rate hikes did two things:

- Raised interest rates

- Sent the economy into a recession, which meant there were less tax receipts as spending and employment fell

Interest costs as a percent of tax receipts hit a peak of 52% in 1985. Usually, the concern when government interest costs rise is that it “crowds out” private investment. Between Q1 1983 and Q2 1985, interest costs as a percent of tax receipts jumped from 43% to 52%. And private nonresidential investment grew 30% during this period.

This framework also helps us think about what could happen going forward.

Looking ahead

Let’s consider the numerator first, i.e., tax costs. It looks like the Federal Reserve is close to the end of its interest rate hikes, assuming we don’t get another upward inflation shock. Now, deficits are projected to remain high over the next decade, around 6% of GDP, but unless we have an economic shock that also prompts a lot more fiscal stimulus, we are unlikely to see the overall level of debt surge higher like it did in 2020.

With respect to the denominator, i.e., tax receipts, it is ultimately dependent on economic growth since tax receipts are a function of that. As long as GDP rises, the debt-to-GDP ratio should remain stable (or fall), and tax receipts will continue to rise. This is why debt-to-GDP fell from 135% in 2022 to 120% in 2020: rather than debt going down, GDP went up. Nominal GDP rose 12.2% in 2021 and 7.3% in 2022.

The key for tax receipts to hold up is for the economy to avoid a recession. And that is our base case right now, that there will be no recession.

So yes, we believe the US debt and interest costs are certainly manageable.