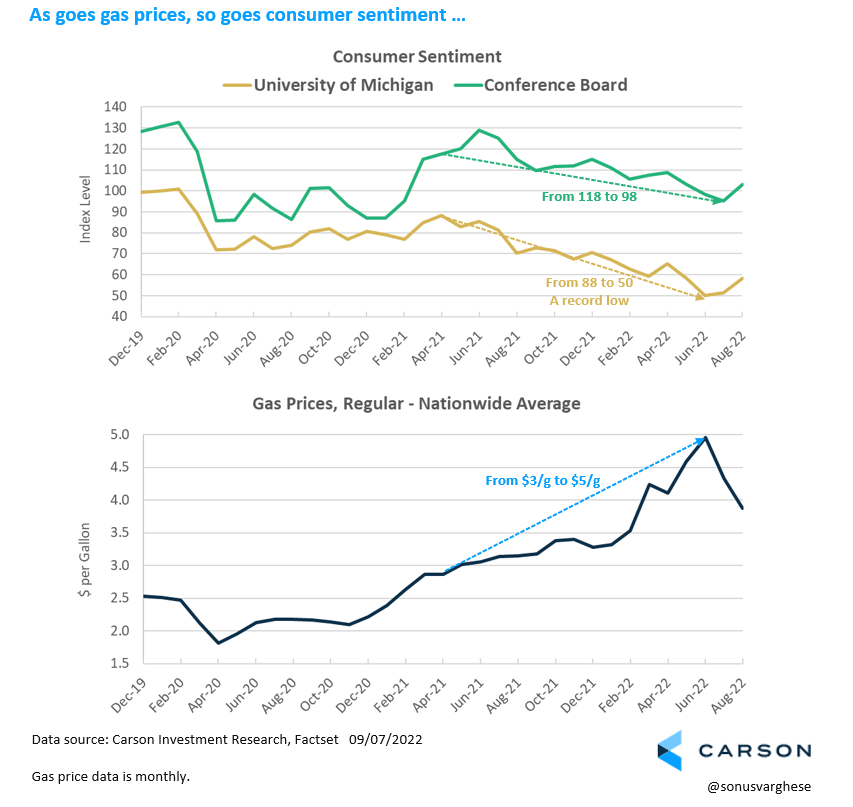

It really is as simple as that, as the chart below illustrates.

Consumer confidence started falling in summer 2021, as gas prices started moving higher. Granted, there were other things going on last summer, like the spread of the Covid Delta variant. But the nationwide average gas price crossed over the $3.0 per gallon mark in May 2021 and continued to steadily rise over the reminder of 2021. All the while consumer confidence moved lower, despite Covid fading into the background and better economic data.

Then at the end of February 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent commodity markets into a frenzy and surging global oil prices pushed gas prices above $4/g. There was some relief in March-April, but issues with refining capacity in the US sent gas prices to $5.0/g by mid-June. That was a 63% increase over a year. No wonder that the University of Michigan consumer sentiment index hit a record low of 50.0 in June – lower than during the height of the pandemic in March 2020 (a low of 72.3) or the depths of the Financial Crisis in 2008 (55.3). Even the Conference Board’s consumer confidence index, which is typically tied to the strength of the labor market, fell significantly, from a level of 118 in April 2021 to 95 in July.

But over the last 4-8 weeks, we’re seeing these sentiment indicators pick up again. Just as gas prices see a steep fall, from $5 a gallon to about $3.80 as of this writing.

Consumer feelings matter, for the economy and for policy makers

As my colleague Ryan Detrick wrote last week, we use sentiment in several ways. Ryan talked about how lopsided sentiment can often act as a contrarian signal. On the economic front, consumer confidence can tell you how consumers are feeling about the economy. And this is important because 70% of the US economy is made up of consumer spending.

Confident consumers can potentially fuel more spending, and economic growth. On the other hand, if consumers are feeling down, they may tend to save rather than spend – especially if they feel that poor economic conditions will eventually impact their personal finances. Which is why even the Federal Reserve considers this an important indicator.

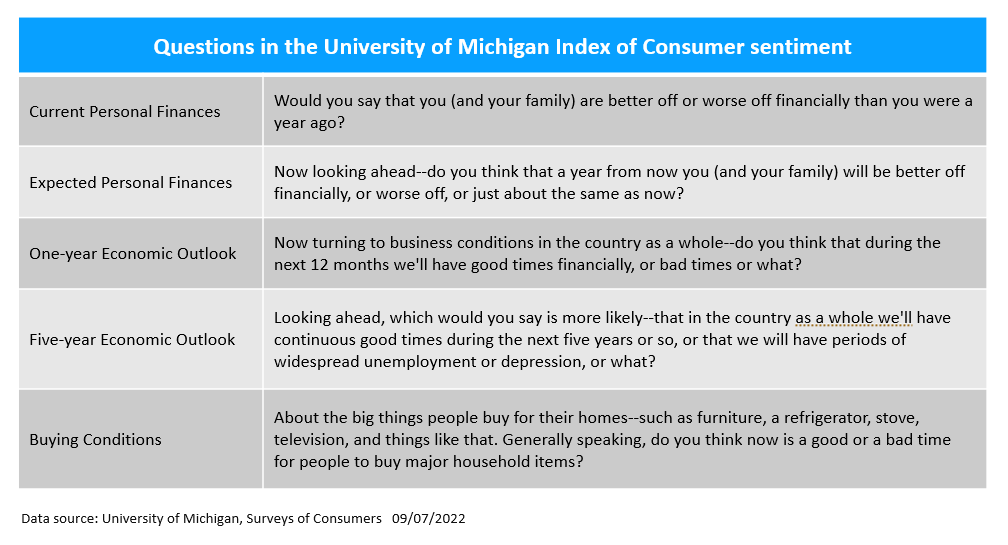

The University of Michigan survey was created by George Katona, a psychologist, in 1946. He wanted to find out how consumers felt about the economy rather than asking questions about how their incomes changed (as was the case before). And the main five questions the survey asks are more or less the same as from back then. The final index is calculated using results from the five questions, weighted equally.

The Conference Board index of consumer confidence was started in the 1960s. It tends to ask consumers more about their feelings about the job market. The current strength of the job market is why this survey is showing slightly better numbers (relative to its history) than the University of Michigan data, which is more tuned to personal finances and inflation.

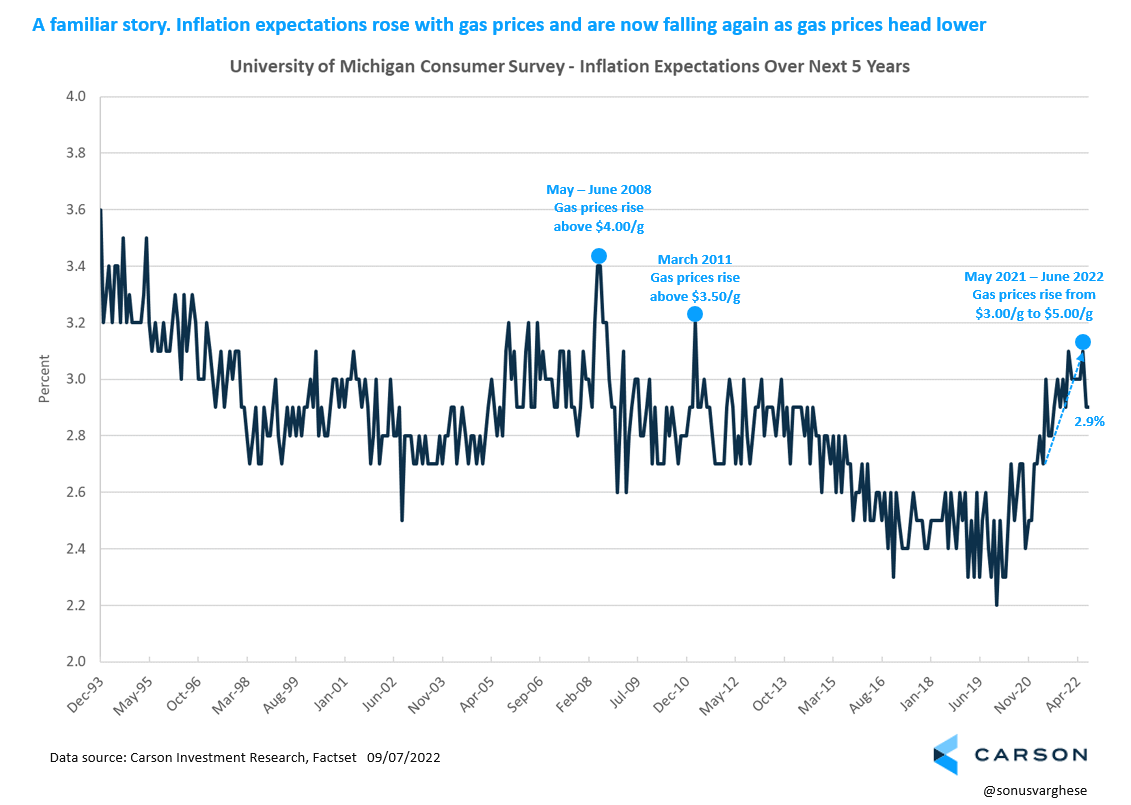

And the inflation question is something the Fed is very tuned to. In fact, as recently as June, Fed Chair Powell pointed to an uptick in longer-term inflation expectations as justification for accelerating their pace of interest rate hikes. Preliminary University of Michigan survey results showed consumer expectations for inflation over the next 5 years rising to about 3.3%, the highest since June 2008 – which alarmed the Fed. They fear that rising inflation expectations will keep inflation higher for longer. The idea is that if consumers expect more inflation, they’d ask for higher wage increases, which would result in more spending and put more upward pressure on prices – leading to a cycle of “spiraling inflation”.

Of course, what happened after the Fed’s June meeting was that the final survey data saw expectations revised down to 3.1%. And they’ve moved even lower to 2.9% over the last two months amid falling gas prices – and that is right at the 3-decade average for this metric. All this to say, consumer feelings about the economy, and inflation, appear very tied to gas prices. The chart below shows how inflation expectations jumped in 2008 and 2011 amid higher gas prices.

An interesting point is that we typically do not see a negative impact on consumer confidence when gas prices are rising from very low levels, like in the aftermath of a recession. For example, consumer confidence steadily increased from May 2020 through early 2021 even as gas prices recovered from about $1.80/g to pre-crisis levels around $2.50/g. 2009 was another example, with consumer confidence rising after the financial crisis while gas prices rose from $1.50/g to 2.60/g. It appears that consumer confidence starts to get negatively impacted only when gas prices breach a certain level.

Bear in mind that these sentiment indicators can trip us at times. For example, consumer confidence fell in 2011 – yes, amid rising gas prices but it cratered in August of that year amid the tumultuous debt ceiling negotiations in Washington D.C. Which ultimately turned out to be a false alarm, in that there was no recession. That may be the case again today. Especially if gas prices continue to fall, or at least, don’t rise from here on out.

That does get to the question as to where gas prices go from here. Something we’re going to write about in an upcoming blog piece. So, stay tuned.