The Federal Reserve has two mandates – “pursuing the economic goals of maximum employment and price stability.” Over the past year, the Fed has been leaning on the side of the price stability mandate, arguing that the labor market is too tight, i.e., beyond maximum employment. Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s mantra has been:

“We must keep at it until the job is done.”

A play off the title of Paul Volcker’s 2018 autobiography, “Keeping at it.” Volcker is the Fed Chair renowned for slaying the demon of inflation in the early 1980s.

Rich Clarida, Powell’s second in command at the Fed from 2018—2022, said:

“Until inflation comes down a lot, the Fed is really a single mandate central bank.”

That works fine until there is a looming financial crisis, which the American economy was probably staring at over the past few days after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB). My colleague Ryan Detrick wrote a very useful piece on the ins and outs of what happened there.

The Fed’s aggressive rate hikes broke SVB

There’s a saying that when the Fed hits the brakes, somebody goes through the windshield. You just never know who it’s going to be.

As Ryan wrote, a big reason for this crisis was the Fed’s aggressive interest rate hikes, where they raised rates from zero a year ago to more than 4.5% by January. Unfortunately, the speed and size of these hikes resulted in losses for SVB (also due to poor risk management on the bank’s part).

The thing is, the Fed has a natural role in maintaining financial stability. At the same time, there is no clear definition for what constitutes a threshold for financial instability, it’s typically not hard to figure out when you’re staring down a crisis, which is what the Fed was facing in September 2008, March 2020, and this past weekend. Thanks to lessons learned in 2008, the Fed acted decisively in 2020 and once again last Sunday – in terms of size, scope, and swiftness of their actions – to prevent a major economic crisis.

Arguably, their actions were successful in 2020, and while the situation is still fluid, they seem to have averted a financial contagion this time around.

The long and short of it is that the Fed’s inflation mandate ran headlong into its crucial role in maintaining financial stability.

Markets are betting that the focus will shift to financial stability

This kind of seems obvious, given what happened over the last few days. And investors have completely flipped their expectations for where they think monetary policy goes next.

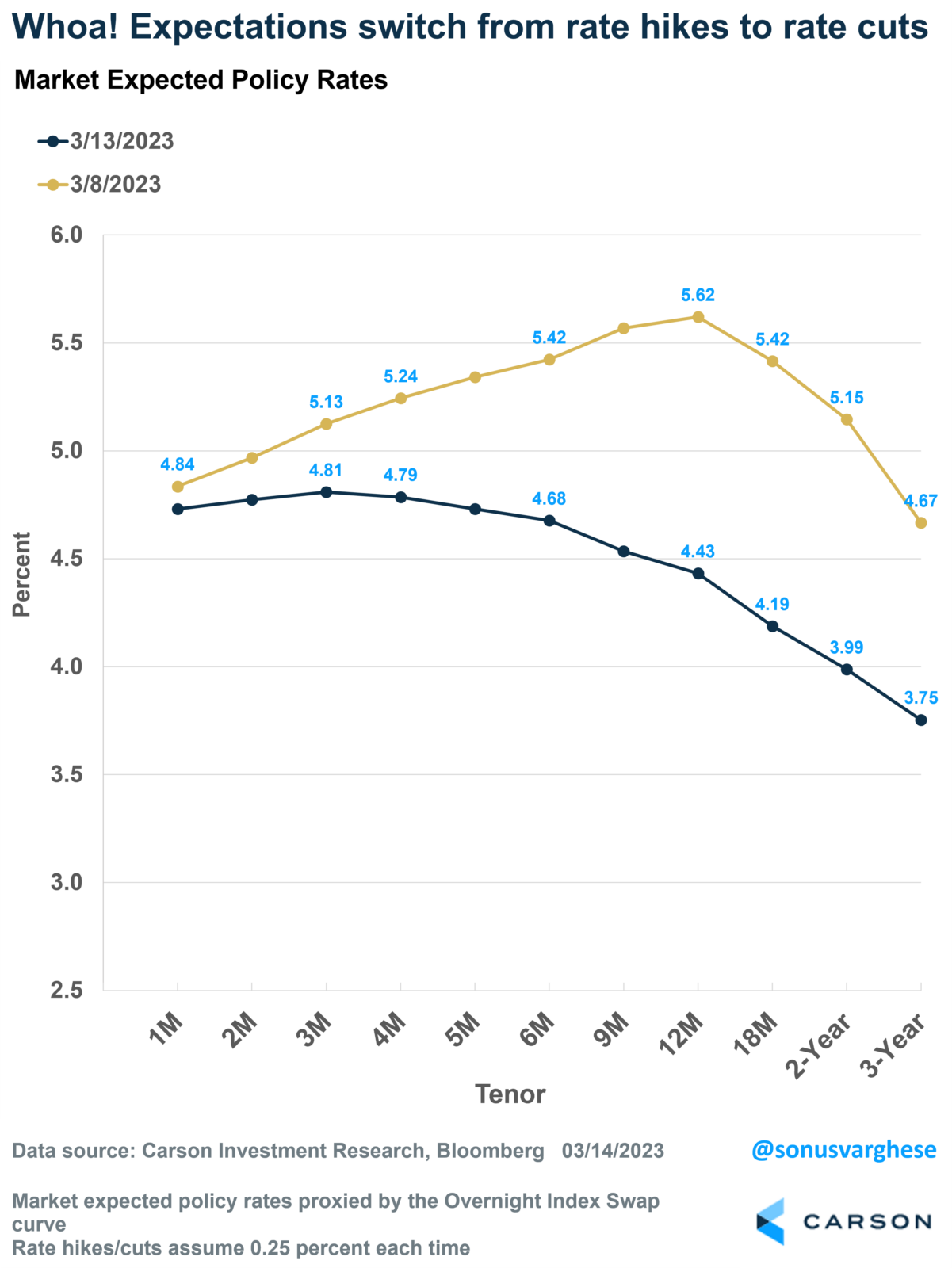

Powell was quite hawkish in front of Congress last week – when he suggested they’re very worried about inflation and could potentially raise interest rates by 0.5% at their March meeting. At the time, we wrote about how it looked like the Fed was panicking. Anyway, investors took Powell seriously enough – pricing in a 0.5% increase in March, a terminal federal funds rate of about 5.6% by the end of this year, and no rate cuts.

Four days of crisis really changed things. Markets are now expecting no rate hike in March and expect the Fed to start cutting rates this year. The terminal rate is now expected to be about 4.8%, which is where we’re at right now. In other words, markets believe the Fed is done with its rate hikes.

And looking ahead to the end of 2023, markets now expect rates to be 1.1%-points lower than what they expected less than a week ago.

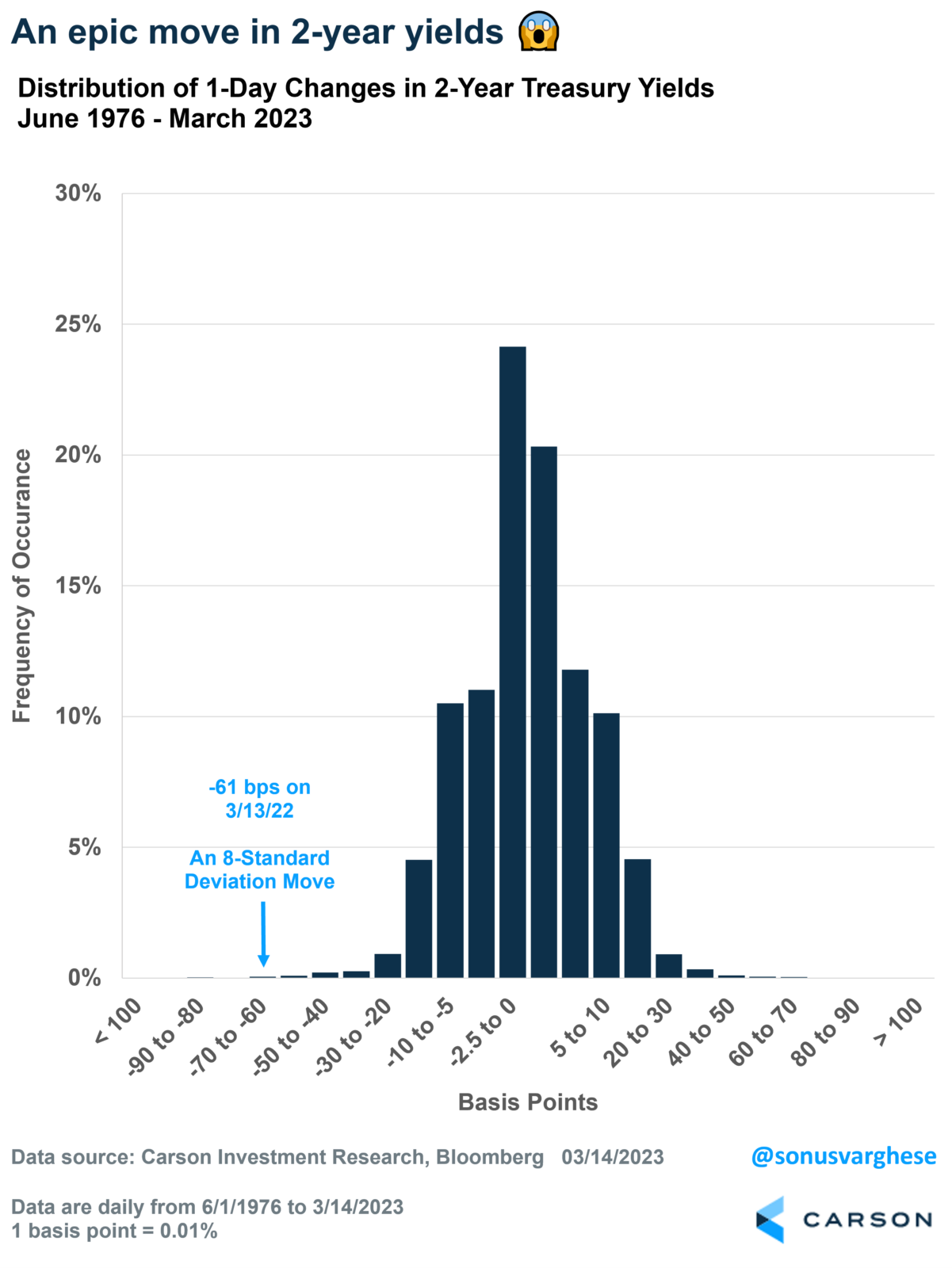

This is an extraordinary shift in expectations. And it manifested in an epic move in 2-year treasury yields on Monday – yields fell from 4.59% to 3.98%! That is an 8-standard deviation move, something you should see only in millions of years. In theory.

The last time we saw a move like that was in the early 1980s, though back then, yields were north of 10%. Yields are less than half that today, and so the -61 basis point move we just saw in 2-year yields is truly historic.

But the Fed still has an inflation problem

But the Fed still has an inflation problem

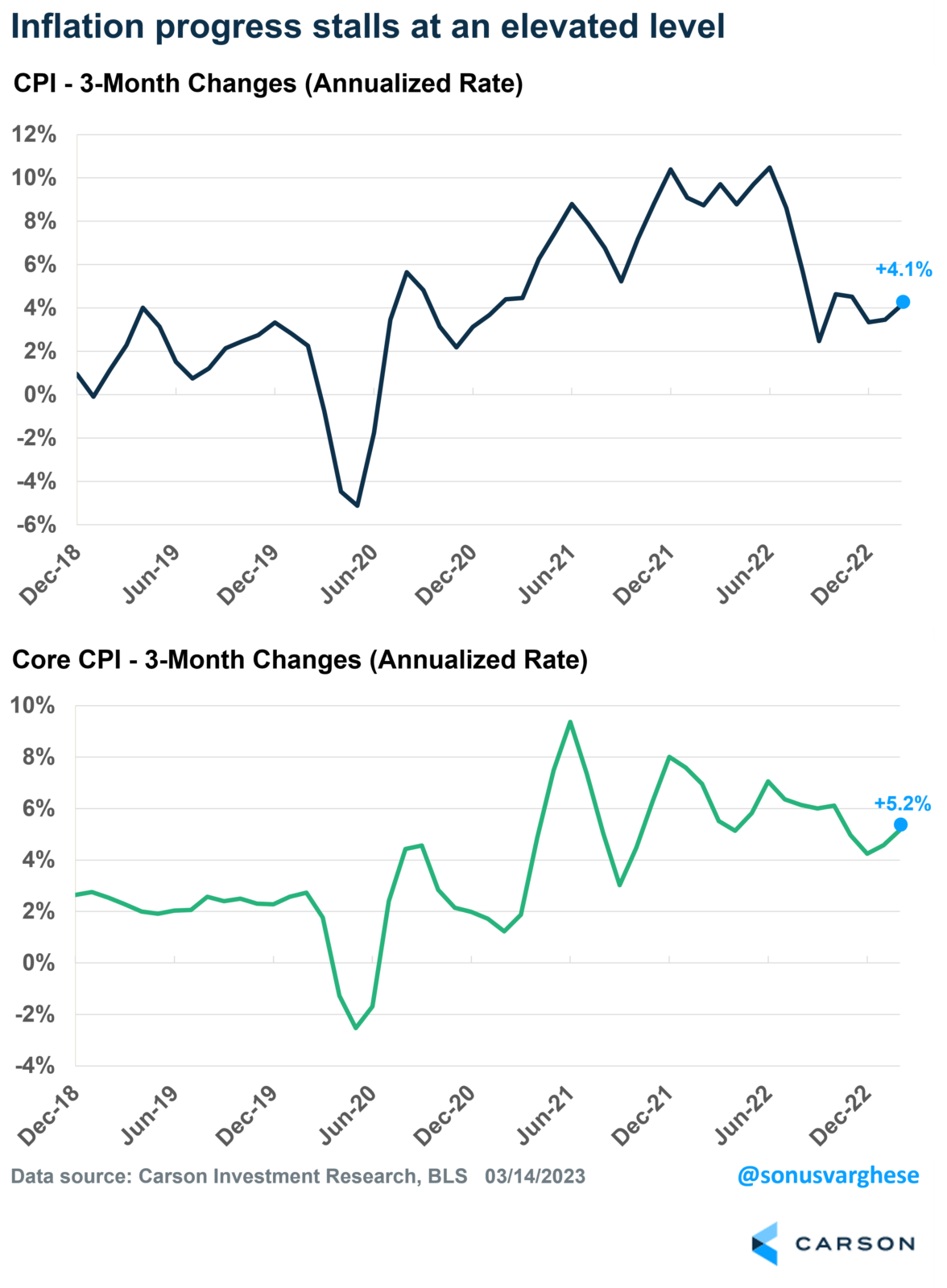

The latest inflation data indicates that inflation remains elevated. Headline inflation rose 0.4% in February, while core inflation (which strips out energy and food) rose by 0.5%, which was more than expected. Monthly changes can be volatile, so it helps to look at a 3-month average. And that’s not a source of comfort either.

Headline inflation is running at an annualized pace of 4.1% over the past three months, while core is running at 5.2%. These are well-off peak levels that were closer to the 10% level. But it’s much higher than the Fed’s target of 2%.

What we believe will happen next

We believe the Fed is unlikely to surprise markets. More so when there are financial stability concerns. So, it’s very likely the Fed does not raise rates at their March meeting. Unless we get another leak to the Wall Street Journal.

In any case, we don’t believe the Fed’s done with rate hikes. Especially when inflation is still too high for their liking.

They’ll probably get back on the rate hike path this summer, perhaps in June, if not even earlier in May. But they may not go as far as we thought prior to last week, with rates topping out in the 5-5.25% range (it’s currently at 4.5-4.75%).

Crucially, the delay may also buy time for inflation data to fall off by itself and prevent a Fed panic. We know that market rents are decelerating, and that should start feeding into the official data soon. There’s also strong evidence that wage growth is decelerating, which means price pressures in the “core services ex housing” category that the Fed has focused on recently, should also ease.